Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

“In fact I thought life was pretty much a losing proposition, and I didn’t mind saying so.”

― Richard Hell, I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp

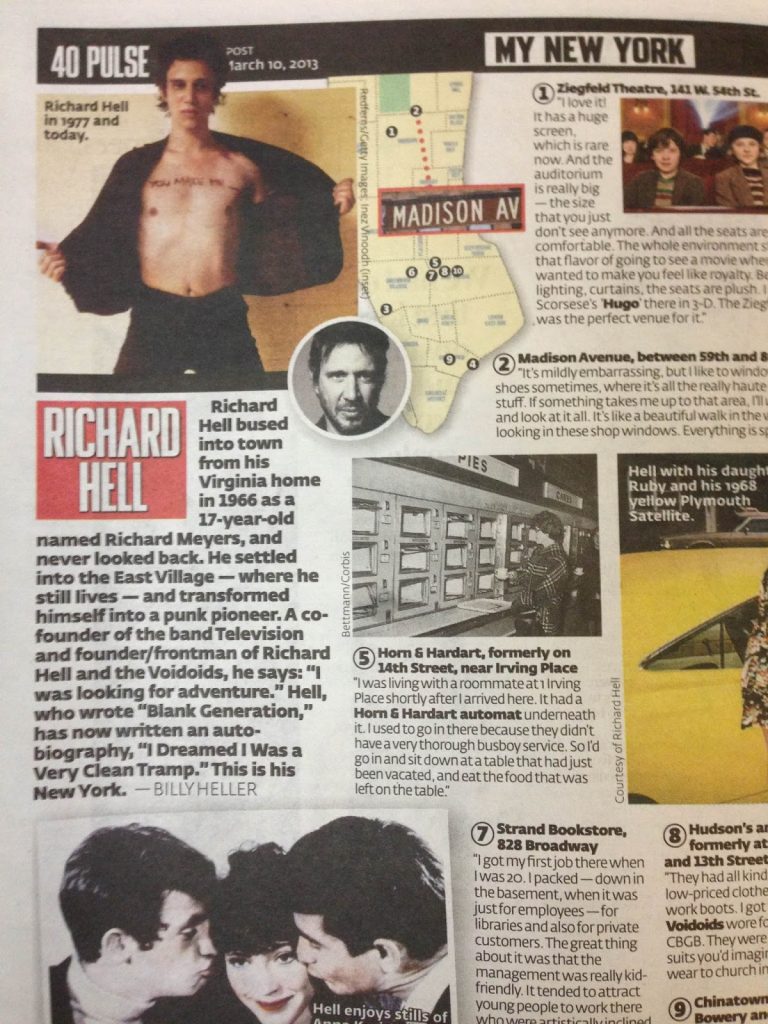

On this day, 18 November, 1976, Richard Hell & the Voidoids stepped onto the low-lit stage of CBGB’s for their debut performance — an unassuming yet pivotal moment in the formation of punk’s visual and sonic identity.

The gig wasn’t a riot, and it certainly wasn’t billed as historic, but in the half-derelict Bowery bar with its tilted sound system and dog wandering behind the bar, something quietly crystallised. A new vocabulary of style, stance, and sound emerged — not yet called “punk,” but already fully charged with its future implications.

Before punk became a headline term, CBGB was simply a refuge for the unfashionable: a narrow room of brick, neon beer signs, and battered furniture. Hilly Kristal’s original intention — “Country, Bluegrass & Blues” — had long been abandoned in favour of whatever the downtown underground needed space for.

By late 1975–76, the room had evolved into a laboratory where Television, Patti Smith, Talking Heads, the Ramones, Blondie, and countless others tested new identities. Hell was already a familiar presence. He’d recently passed through Television (with Tom Verlaine) and then The Heartbreakers, but the Voidoids represented his complete artistic vision — raw, literary, jagged, and alive with restless invention.

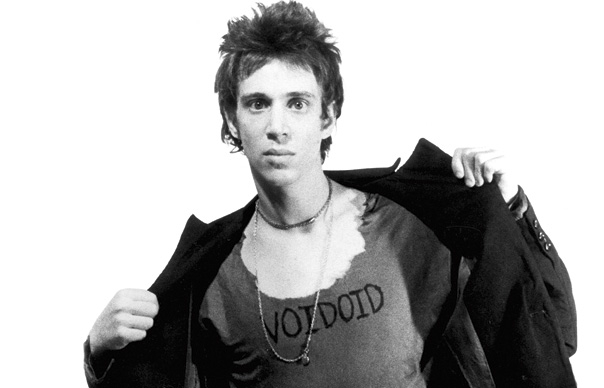

Regulars recall Hell arriving with shirts he had sliced open, scribbled on, and held together with safety pins — not as shock-theatre but as an honest reflection of financial reality and creative impatience.

Photographer Roberta Bayley later remarked that Hell looked “like he came from the future and the past at the same time,” a description that frames this gig perfectly.

This line-up combined nervous intensity with intellectual sharpness. Quine’s guitar cut like stray electricity; Julian added structure and depth; Bell brought discipline welded to street-level power. Hell — part poet, part provocateur — held the centre with cracked charisma.

Audience accounts describe the early Voidoids sets as:

“Love Comes in Spurts” and “Blank Generation” were already appearing in the setlist — songs not yet recorded but already functioning as declarations.

Blank Generation, in particular, articulated a new stance: self-definition through refusal, a kind of existential autonomy delivered with sardonic bite.

Malcolm McLaren encountered Hell’s look during his mid-’70s New York visits, and carried it to London:

When the Sex Pistols arrived fully formed in 1976–77, Hell’s imprint was unmistakable, even if rarely acknowledged with clarity.

Hell fused Beat fragments, French symbolism, détournement, and street poetry into rock music.

His approach treated the stage as both performance and deconstruction — art as immediacy rather than posture.

This gig helped codify CBGB not simply as a venue, but as the epicentre of a global subculture, where the unpolished and unexpected were given just enough space to become defining.

(as they circulate through the oral archives)

Whether or not these anecdotes are exact, they map the emotional truth of the night: humour, tension, invention, and a sense of imminent shift.

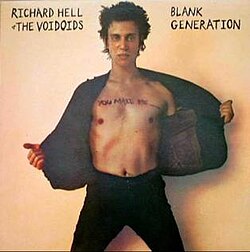

In the months that followed, the Voidoids recorded Blank Generation, one of the enduring documents of early punk’s intelligence and abrasion.

Hell’s persona — fragmented, knowing, vulnerable, and confrontational — seeded an entire generation of musicians, stylists, designers, and writers. His influence travelled outward into:

He didn’t chase mass recognition; he catalysed a movement.

The debut show of Richard Hell & the Voidoids at CBGB’s stands today as a hinge-point moment — one of those events whose significance is only visible in retrospect.

From a dim stage on the Bowery emerged an aesthetic that would travel across oceans, reshape fashions, and influence generations of outsiders.

On this day, a small room witnessed the beginning of something vast.